Text | LEUNG Ping Wa

Photo | Hulu Culute, ISD

Kwun Tong District is bordered by Wong Tai Sin in the west, by the foothill of Kowloon Peak (aka. Fei Ngo Shan) in the north, and Lei Yue Mun in the east. Covering more than 1,100 ha, including Choi Hung, Ngau Tau Kok, Kwun Tong, Shun Lee, Sau Mau Ping, Lam Tin, Yau Tong, and Lei Yue Mun, the district has a population of about 700,000 and a history that stretches back to the Song dynasty (960–1279).

Around the time of the PRC’s founding in 1949, many refugees arrived and settled all over the hillside in slums called “squatter settlements”. Kwun Tong gradually grew into an industrial zone, becoming the first satellite town in Hong Kong and the first region to host a district council.

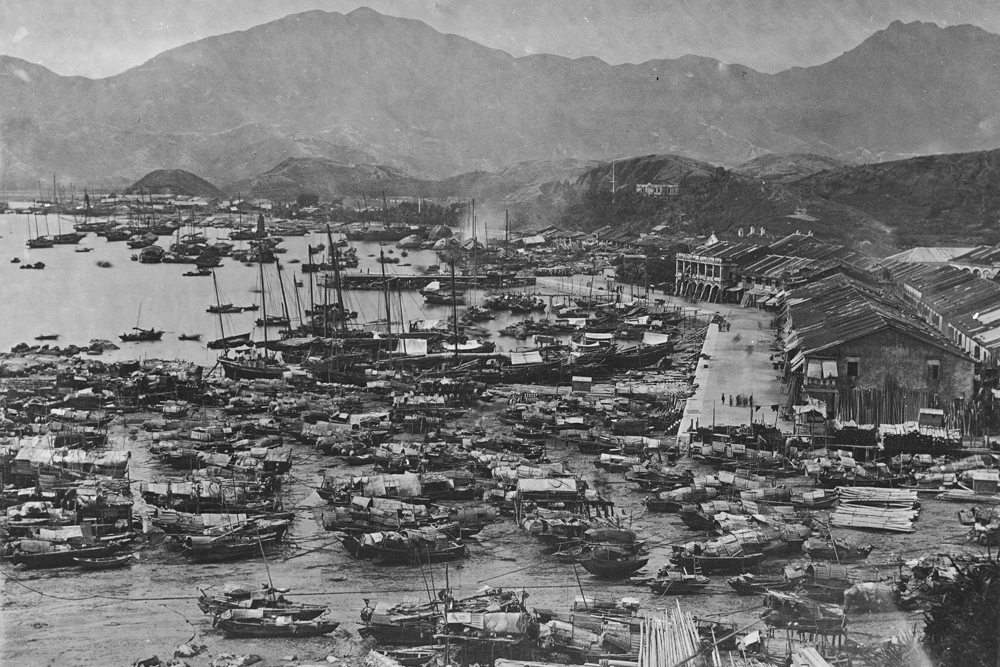

Kwun Tong of Yore

Formerly known as Gūn Fu or Gūn Tòhng, variations on “mandarins’ salt pans” from the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), the name Kwun Tong was formalised in the 1950s to a homophonic “Scenic Pond”. With little development until the 1950s, the district was largely uninhabited from Ngau Tau Kok to Yau Tong Bay, with a minuscule population scattered among the rolling hills. Residents mainly worked on stone miners, agriculture, aquaculture, ceramics, and (fire) matchmaking.

In the fifties, the government reclaimed land from the sea south of Kwun Tong Road to develop an industrial zone; residences were built on the hillside to the north for the workers. The business and service centres are located at Yue Man Square.

Traditional Industries

Saltmaking and stone mining were the heart of traditional industry in Kwun Tong District. The “stone crushing” trade, da sehk , was the industrial and economic mainstay of the district. Concentrated in the Sze Shan area (Ngau Tau Kok, Sai Tso Wan, Lei Yue Mun, and Cha Kwo Ling), it came to the fore in the early 19th century and gradually declined by 1967.

Japanese Occupation Period

In December 1941, British and Japanese forces fought the Battle of Hong Kong, leaving traces of war at Devil’s Peak. After the British surrender, the Japanese Army divided Hong Kong into 28 districts by population. Kwun Tong went under “Kai Tak District”. Many guerrillas lurked at Lei Yue Mun and Cha Kwo Ling.

Educational Developments

In the early days, education was provided through private tutorage (si suhk ) or free schools (yih hohk ). The Tin Hau Temple at Sai Tso Wan, for example, ran a Sze Shan free school which was rebuilt at Cha Kwo Ling as Sze Shan Public School in 1952. Hoi Bun School was completed at Lei Yue Mun in 1946. In the 1960s, many rooftop schools appeared in Kwun Tong district; from the seventies onward, the Government has built many primary and secondary schools with standalone school buildings.

Transport Developments

The district was largely dependent on ferries in the early years, with connections linking Shau Kei Wan, Lei Yue Mun, Cha Kwo Ling, and Kwun Tong. Before the 1960s, the main overland route was Ngau Tau Kok Road; the present thoroughfare Kwun Tong Road was completed in 1962.

Construction of the Mass Transit Railway Kwun Tong line began in 1975, with the line extended to Central on 12 February 1980. In 1989, Eastern Harbour Crossing and Lam Tin MTR station were completed in succession. In 1991, the Kwun Tong Bypass opened, improving traffic in the district in the process.

Origins of Place Names

Ngau Tau Kok

Ngau Tau Kok (“Cattle Head Cape”, alt. “Cattle Horn”) is a cape located between Kowloon Bay and Kwun Tong Bay, and is shaped like a cattle horn which gives rise to the name.

Lei Yue Mun

Lei Yue Mun (“Carp Pass”) is a sea channel littered with skerries and reef – some of which look like carps.

Cha Kwo Ling

Behind Sze Shan Public School is a round mound which looks very much like cha kwo tea snacks. There are many parasol leaf trees with which you can make the snacks too, hence the name.

Sai Tso Wan

A bay covered with seaweed, which the Hakkas called se chaau, or sai chou in Cantonese, hence Sai Tso Wan.

Devil’s Peak

Devil’s Peak (Mo Gwai Saan ) was originally called Black Hill (Haak Saan – now Black Hill refers to another mountain called Ngh Gwai Saan ); or Gai Poh Saan (“Hen’s Hill”).

Pirates roamed the area during the Ming and Qing dynasties, and the robbing of travelling merchants gave rise to the diabolical name. Battery forts were constructed in the early 20th century, giving it yet another name Paau Toih Saan (lit. “Fortress Hill”). Nowadays the location is usually called Devil’s Peak.

Ngau Chi Wan

Apparently, near the village of “Cattle Pool Bay” was a big pool shaped like a cow in water.

Lam Tin

“Blue Fields” was in the salt-making region, but Haahm Tihn Saan or “Salted Earth Hill” was deemed improper. In 1970, the Hong Kong Government furnished a classical reference where “the mountains of Lantian, Shaanxi produce beautiful jade” and changed the name to Lam Tin.

Yau Tong

In 1947, the Asiatic Petroleum Company bought land near Cha Kwo Ling to build an oil depot, and the another lot for expansion in 1954 at what is now Laguna City: hence “Oil Pond”.

Sau Mau Ping

The mountain was once covered in sou maauh chou (uncertain etymology: possibly “perilla”, “cogongrass”, or “growing reeds”). This sounded like the ominous Sou Mouh Pìhng or “Tomb Sweeping Plains”, which led to the new name Sau Mau Ping, “Lush and Graceful Plains”.

Monuments and Customs

Kwun Tong Distr ict hosts many histor ic buildings, such as the two-century-old Lords of the Three Mountains temple (Sanshan Guowang Temple); the Tin Hau temple at Lei Yue Mun, probably built in 1753 (18th year of the Qianlong reign); the other Tin Hau temple that was originally at Sai Tso Wan before relocating to Cha Kwo Ling; and the battery fort on Devil’s Peak at Cha Kwo Ling, built against Japanese attacks.

There are several important customary festivals in the district, such as Tin Hau’s birthday (23rd day, 3rd Lunar month), Hungry Ghost Festival (14th day, 7th Lunar month), and the birthday of “Monkey King” Sun Wukong (16th day, 8th Lunar month). All attract large crowds to the celebrations.

Post-war Development

Kwun Tong developed into an industrial area from the 1950s onwards, at tracting many Teochews (Chaozhou), Hoklos, and Hakkas. The native bonds fed into a neighbour ly

community feeling. Still, the living environment was poor and so was law and order, resulting in the derogatory term “Red Indian district”.

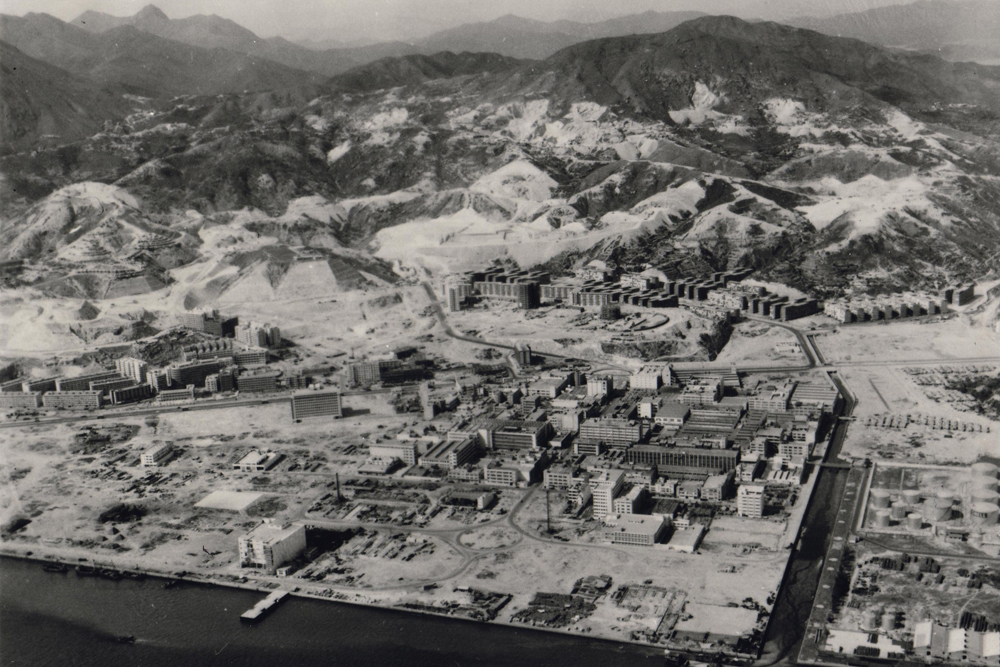

Reclamation from the Sea

In the 1950s , the government decided to reclaim land from

the seaside south of what is now Kwun Tong Road in an effort to develop industry. Phases I and II of the project ran from 1956 to 1959, creating 33 ha of land around the present Kwun Tong Road, Chong Yip Street, Hoi Bun Road, and Tsun Yip Street.

In 1959, the third phase commenced east of Kowloon Bay and was completed in 1967. Many street names have an industrial air to it: Chong Yip and Tsun Yip mean “Start-up” and “Galloping Trade” respectively.

Industrial Development

From the 1970s to mid-1980s, the area south of Kwun Tong Road became Hong Kong’s

largest industr ial area, with numerous factories churning out hardware, garments, electronics, plastics, wigs, and household goods among others. Emerging products include audio equipment, TVs, and computer. During China’s reform and opening up phase, many manufacturers traded, exchanged, and otherwise worked with coastal areas in China in an adrenaline shot to both economies.

At that time, Kwun Tong’s industrial employment accounted for one-third of Hong Kong’s total, with 22,000 in the electronics industry, 18,000 in textiles, 10,000 in plastics, and 6,000 in hardware. The government built public housing villages such as Upper and Lower Ngau Tau Kok Estates, Lam Tin Estate, Sau Mau Ping Estate, and Shun Lee Estate to house squatter dwellers and the large industrial population.

Woodyards and Shipbuilding

In the 1960s, shipyards such as Wang Tak and China made their debut at Yau Tong Bay, peaking at about 26 shipyards and woodyards. In the 1980s, Hong Kong started to feel the heat from competitors in China, Japan, South Korea and other economies as the operating environment deteriorated. Shipyards and wood mills closed one after another.

Treatment of Workers

Child labour was widespread in the early days of industrialisation. Workers worked long hours for meagre pay. As the 1970s to 1980s went on, the number of factories ballooned. Wages and welfare were improved to retain workers.

Environmental Pollution

Industrial development has brought not only economic growth but also serious pollution to Hong Kong. From the 1960s to 1990s, many factories discharged industrial wastes nonchalantly, causing pollution to the detriment of residents’ health.

Industrial Decline

Chinese economic reforms began in 1978. Zhuhai , Shenzhen, Shantou, and Xiamen became special economic zones which carried out processing procedures, joint ventures, and small-scale wholly-owned operations. Meanwhile in Hong Kong, increasingly strict labour laws, vigorous industrial action, sharp rises in factory prices and rents, and the dawn of financial and service industries stimulated demand for labour and costs for manufacturers. Hong Kong manufacturers rushed to move their factories to mainland China.

In 1970, the total output value of the manufacturing industry accounted for 30.9% of Hong Kong’s gross domestic product. Between 1980s and 1990s, it was only 22-24%. The proportion of manufacturing in total employment in Hong Kong dropped from 46% in 1980 to less than 10% in 2002, a testament to the decline of industry in Hong Kong.

Business Transformations

Industrial land at Kowloon Bay and Kwun Tong was rezoned to “business” use in 2001, allowing industrial buildings to be repurposed for office use or converted into commercial, office, shops, and hotels. On top of small and medium-sized enterprises, designers, musicians, artists, and collectors have all opened studios and shops in old industrial buildings. The ensuing creative and cultural business district has injected a new and vibrant impetus into Kwun Tong. Large shopping malls like APM and MegaBox have become excellent entertainment destinations for residents. The Zero Carbon Building opposite MegaBox is a pilot project with a landscape area to showcase the potential of zero-energy building.

In early 1998, the Land Development Corporation (now Urban Renewal Authority) proposed a redevelopment project for Kwun Tong City Centre. The reconstruction of Yue Man Square began in the 2010s.

Development Opportunities

Hong Kong’s Second Core Business District

With Kai Tak Airport relocated and manufacturers shifting north of the border, Kwun Tong is left with a lot of space. However, Hong Kong’s financial and services industry continues to thrive, and commercial cores on Hong Kong Island are no longer able to cope with the demand for quality office buildings.

In his last policy address in 2011, Chief Executive Donald Tsang proposed “Energizing Kowloon East”, a plan to transition Kai Tak Development Area, the Kowloon Bay Business District, and the Kwun Tong Business District – all in Kowloon East – into a second core business district (CBD) to maintain Hong Kong’s status and development in the long run as an international financial centre.

Energizing Kowloon East

The Energizing Kowloon East Of f ice was established in 2012 when it proposed ten major tasks to improve live ability in the area, such as improving the waterfront area next to Hoi Bun Rd, transforming the open stormwater channel on King Yip St from Kwun Tong Nullah to “Tsui Ping River”, and improving pedestrian accessibility in Kowloon Bay and Kwun Tong.

Kai Tak Development Plan

In March 2009, the government rolled out the enormous Kai Tak Development (KTD) plan at the site of the former Kai Tak Airport. “The plan envisages turning Kai Tak into a distinguished, vibrant , at tractive and people-oriented community by the Victoria Harbour.”

Totalling over 320 ha, KTD includes more than 49,900 public and private housing units plus approximately 2 million sqm for commercial and office purposes. With 168 ha of land in Kwun Tong and Kowloon Bay Business Districts, Kowloon East may yet become another CBD in the city.

Smart City Pilot

In the 2015 Policy Address, the government proposed to use Kowloon East as a pilot site to rebuild Hong Kong into a smar t city. In response to the local environment, eight Proof Of Concept Trials were undertaken. “Smart Crowd Management System”, “Persona and Preference-Based Wayfinding for Pedestrians”, and “Real-Time Road Works Information” were completed in mid-2019. The rest includes “Energy Efficiency Data System”, “Multi-Purpose Lamp Post”, and “Real-Time Road Works Information”, which are still being tested and are expected to be completed in 2020.

Summary

At present, the Kai Tak development plan and the reconstruction of Yue Man Square are in full swing. As Yau Tong Bay Comprehensive Development A rea r amps up, and new residential blocks are completed at Anderson and Cha Kwo Ling, a new look will descend on Kwun Tong District.

1“Xianggang quantu” [Atlas of Hong Kong]. Xianggang nianjian[Hong Kong Almanac] (1950). Wah Kiu Yat Po.

2 Energizing Kowloon East website. Background information on the EKE Office: https://www.ekeo.gov.hk/tc/about_ekeo/background.html

3 https://www.ekeo.gov.hk/tc/smart_city/index.html

The “squatter area” in Ngau Tau Kok was built in 1967, next to the factory plant of Amoy Canning Corporation, Ltd. The seaside was littered with squatter houses and small shipyards doing repairs

Sam Shan Kwok Wong Temple (“Lords of the Three Mountains”) next to Ping Shek Estate

Many houses stood in Kai Tak in the early years, and numerous large-scale development projects are in the works.

Joss sticks smoulder away still at Tin Hau Temple, Cha Kwo Ling, reflecting the traditional faiths of its residents.

Cha Kwo Ling still hosts its share of squatters and stone cottages today. New developments are presumably afoot.

Devil’s Peak Battery retains many relics and attracts many tourists over the holidays.

In the early years, the villagers of Sam Ka Tsuen made a living by stonecutting. It developed into what is now a tourist hotspot, luring tourists in with seafood and other gourmet options.

Kwun Tong South was reclaimed from the sea in the 1950s, and the government was determined to develop it into the largest industrial zone in Hong Kong.

Industry took off in Hong Kong in the 1960s and 1970s, employing many local workers and kickstarting both the economy and local consumption.

The electronics industry used to be an important domestic industry. Assembly and processing for foreign businesses was a rite of passage before homegrown research and development could take place.

As China opened up in the 1980s, many local factories moved up north across the border. Only a handful of traditional industries are still in business today.

In recent years, many industrial buildings have been demolished to make way for large-scale commercial buildings as part of the larger economic transformation

In coordination with the neighbouring Kai Tak Development, the government proposed a pilot programme to develop Kowloon East into a smart city.