Text|Lee Ying Yi

Photo|Wong Wai Kit

According to the 1911 census of Hong Kong, the population of Sai Kung was merely 512 at that time; but the recent 2011 census registered a total of 11, 927 residents in Sai Kung. After a century, this tiny peninsula at the tip of New Territories East has transformed from villages to market; and from market to a town. These changes intertwined with the historical milestones of Hong Kong as well as the fate of an ethnic group.

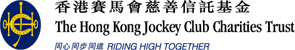

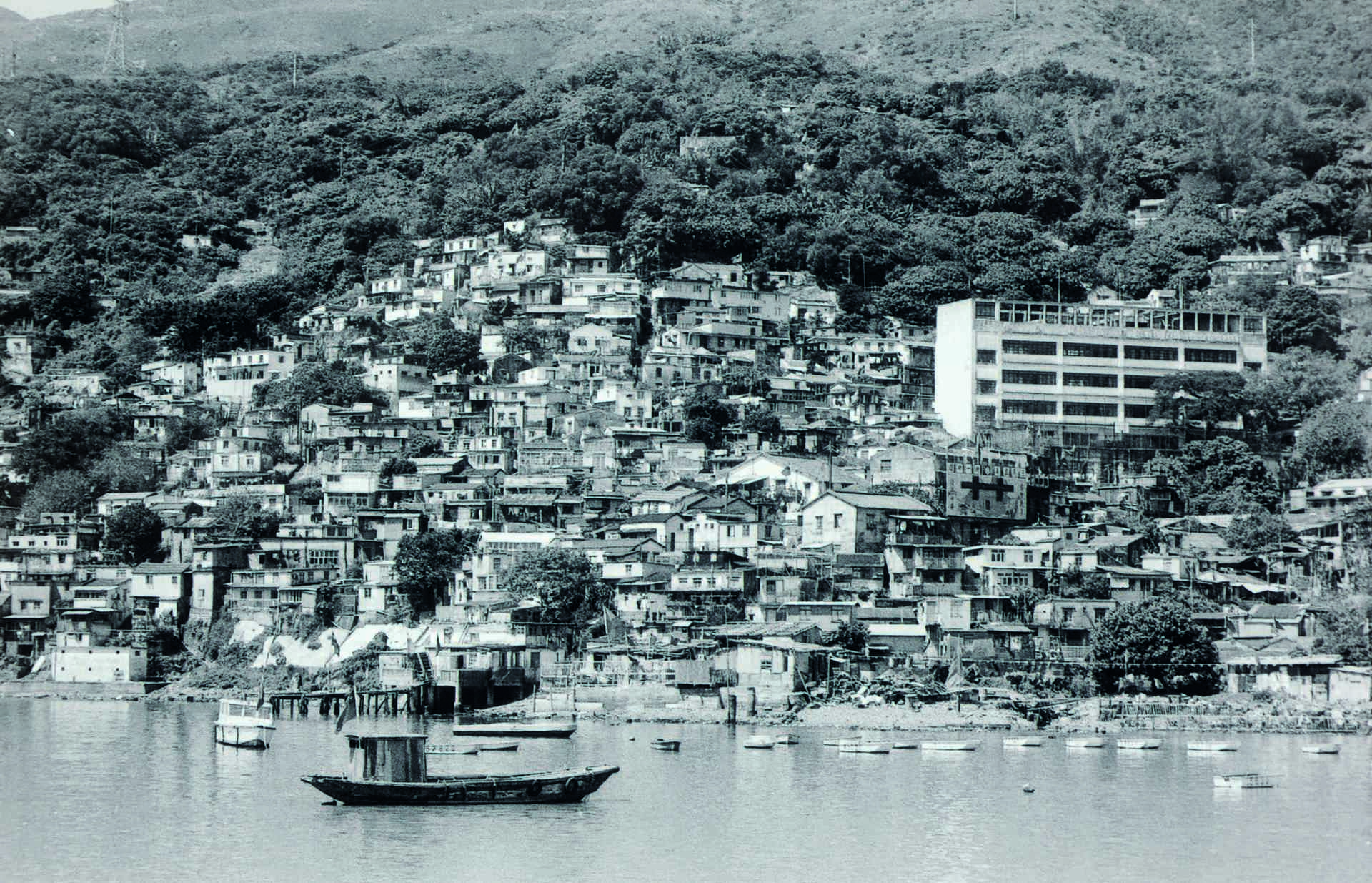

Historical record indicates that the Sai Kung Market was already established in the early twentieth century. At that time, the Tin Hau Temple we see today was immediately facing the ocean, and was nicknamed Miu Kok Tau (i.e. temple headland). The households lived on Fui Yiu Lane and Sai Kung Road of today and spread to Main Street and Ching Tai Street, inside there were vegetable gardens, pig pens, grain drying yards and shops. The intersection of the two main streets formed an open space right by the waterfront, and that is the current Market Street and Hoi Pong Street. In the old days before any reclamation had taken place that was the most spacious and widest stretch of open space in Sai Kung.

People congregated in the market on Tam Tsai Ping before WWII.

After the war, a road was opened

The waterfront open space was called Tam Tsai Ping because people often carried their crops and fish harvests with carrying poles to trade in the buzzing market. The market provided lots of business opportunities for retailers, traders and wholesalers alike. Near the mountain, there was Yau Ma Po Village, and, near the sea, there was Fui Yiu Ha Village, both quickly grew out of their original rural style, and blended into the commercial development, this laid the foundation for Sai Kung to exist without any old villages except only a number of old streets. Most of these features are still discernible. Lee Fook Hong, the current President of the Sai Kung Kaifong Association mentioned an old stone plaque inside the Tin Hau Old Temple, “In 1916 Bingchen year, a fundraising campaign was launched to rebuild the temple, the list of people who made contributions had been engraved onto this stone plaque. The fact that the majority of donations came from many business firms indicated that commercial activities prospered.” Even more business development had taken place after the war when the Japanese expanded the military roads during occupation and the Hiram’s Highway was built. This new road goes from Sai Kung directly to Kowloon, therefore, more businesses and shops began to congregate in Sai Kung, turning it into a transportation hub. Grocery stores, restaurants, rice shops, sieve rice shops, sundries shops, tailors, and even funeral homes were all doing business in Sai Kung. Hakka people, Tanka people, Chiu Chow people, and businessmen from San Wui all gathered for a living. The Sai Kung Chamber of Commerce formed in 1941, has evolved into the Sai Kung Kaifong Welfare Association which united the neighborhood residents and the Sai Kung Rural Committee which involved in local administration, they have been serving the community until today. The founding president of the old Sai Kung Chamber of Commerce Lee Siu Yum was in fact the grandfather of Lee Fook Hong.

Found Kaifong Association and Rural Committee, A Villager became a businessman

The name Lee Siu Yum is famous even in Sai Kung today. The primary school started in 1952 has later developed into Lee Siu Yum Memorial School. The Man Yee Wan Sha Tsui San Tsuen memorial archway also carries the calligraphy inscription and signature of Lee.

“My grandfather was a teacher in our village (Lan Nai Wan) in his younger days, later he came to Sai Kung and did a lot of things with other seniors to help the residents. He even set up a public scale for the sake of settling trade disputes and offered free education in the temple.” Lee Siu Yum was the owner of Yan Sang Tong Herbal Shop; he also served as the Kaifong Association President and Rural Committee Chairman for many years. Actively involved in the welfare of Sai Kung in his lifetime, Lee had made significant contributions and resulted in leading his entire village to relocate here.

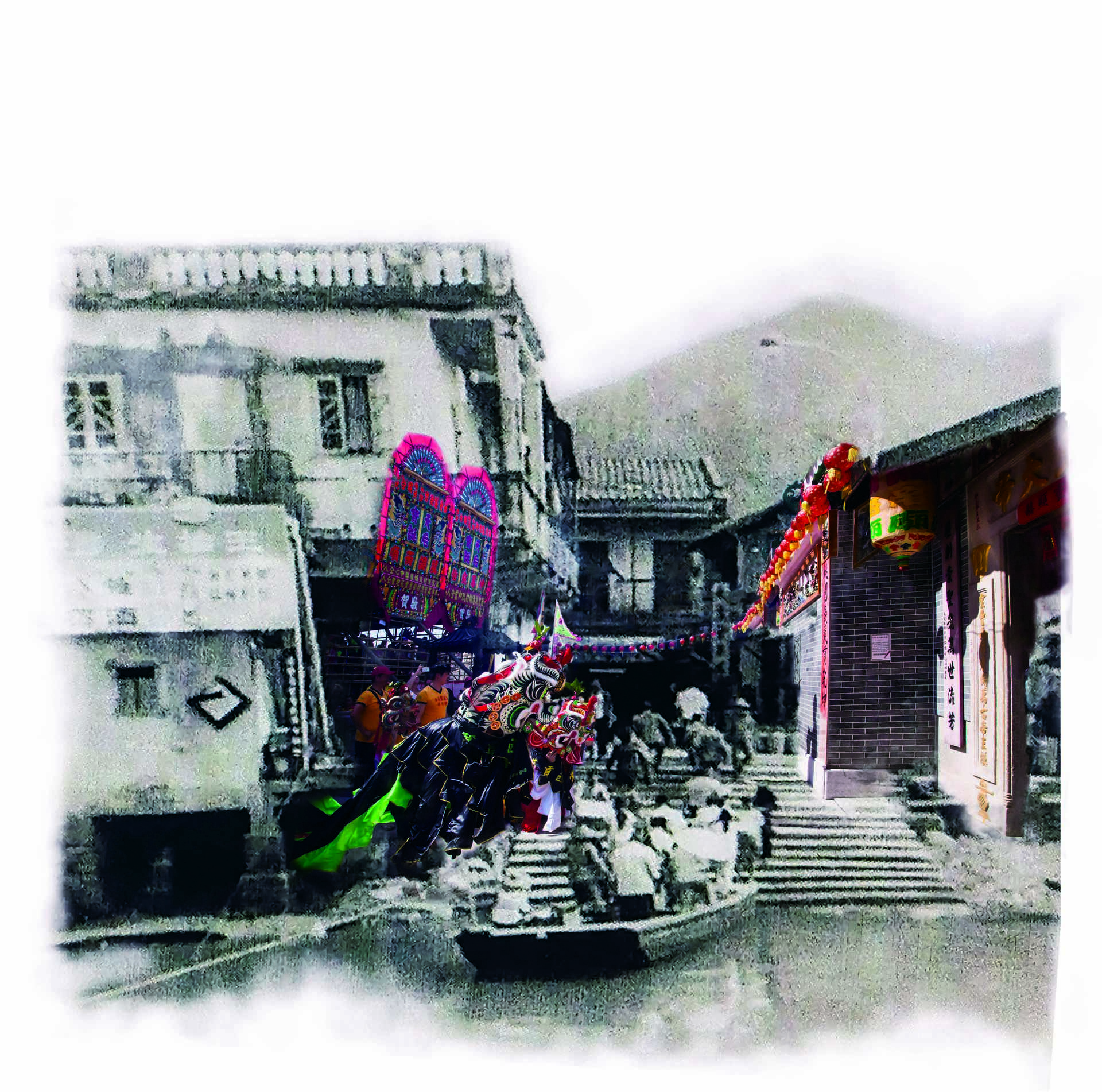

The Lee clan is a Hakka ethnic group; their ancestors had migrated southward from Huizhou during the Daoguang period of the Qing Dynasty. Initially they settled in the northwestern shore of the Kwun Mun Channel in Sai Kung, and opened a village in an area formerly known as the old Lan Nai Wan and called it Lee Uk. Together with the neighbouring Chow Uk, Chan Uk, Man Uk, they were all living on doing farming and fishing. In 1969, the Government picked the Kwun Mun Channel site for High Island Reservoir development; huge dams had to be built to block the seawater and salt water pumped out to make room for fresh water. As a result of these major infrastructural constructions, all the houses, the ancestral halls, the Tai Wong Pak Kung Temple, farms and trees in Lan Nai Wan and Sha Tsui Village to the east had to be submerged.

At that time Lee Siu Yum was in his seventies, accompanied by his nephew Lee Kwai and Lee Yun Sau, they proactively negotiated with the District Office and asked for just compensation and resettlement for the local villagers as well as villagers who were working overseas at the time.

Old villages Submerged in the new reservoir Temple Headland reclamation

Today, Lee Siu Yum and Lee Yun Sau have passed away; Lee Kwai is now too old to be disturbed. For the rest of the story, Lee Kwok Wah, son of Lee Yun Sau and the former representative of Man Yee Wan New Village, says: “Our village was very poor, it was too difficult to live on farming and fishing alone, so many of us had to go to work overseas, most went to the UK. It was easy to migrate to England; anyone born in Hong Kong could get a British passport, so many left and worked in the kitchen of the restaurants there. There were also quite a few who went to the United States, or to Sandakan in Malaysia, and actually traded themselves with human traffickers, sold themselves as pigs so to speak, to become hard labour, sawing timber, or worked in stone quarries and rubber plantations. They will be working there for decades, and we hardly get any news from them even after they got married and had raised a family there.” During the preparations for relocation of the village, old folks spoke of these relatives who went abroad and wished to spread the message through to them one way or the other. “We had placed search notices in Malaysia local newspapers for two years, to inform them that village relocation will soon take place, and to invite them back for reunion as well as to claim back their belongings.” Ironically, meanwhile, the reservoir construction work which had started began to affect the normal livelihood of the local villagers due to disruption of the waterways; there was no fish to catch and no water for farming. As a result, many had to follow the footsteps of their forefathers and left for overseas.

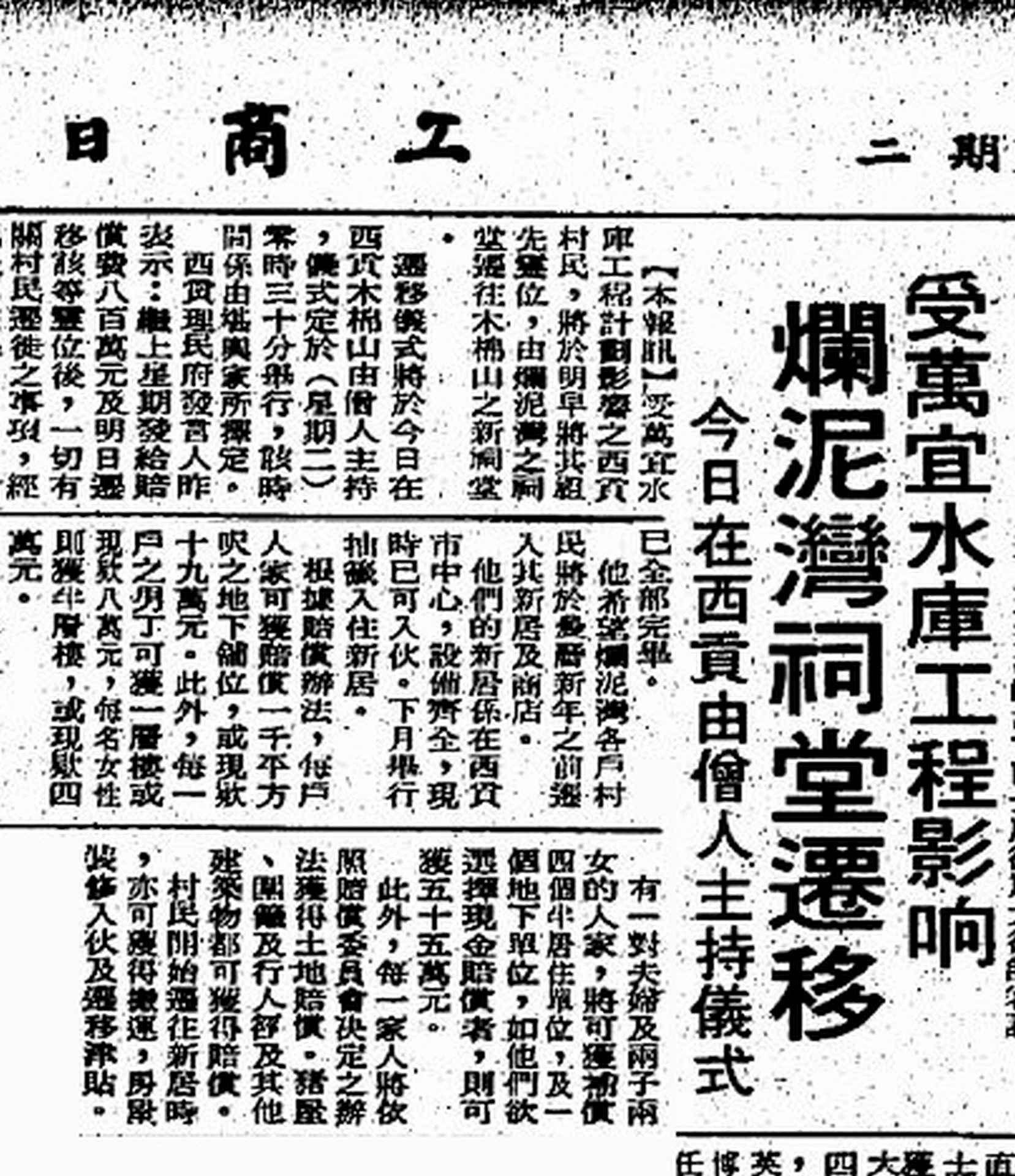

In 1974, the Government built ten five-storey buildings on the newly reclaimed land in front of the Tin Hau Old Temple in Sai Kung Town for the resettlement of villagers in the old Lan Nai Wan area. In the same year, Kung Sheung Daily News in Hong Kong reported that every male villager could obtain a compensated flat or HK$ 80,000 in lieu, while each female villager could obtain half a flat or HK$40,000 in lieu. To top it off, every household was also awarded a shop on the ground floor to start a business or HK$190,000 in lieu as compensation. In early 1975, a total of 57 households from Lan Nai Wan Village and Sha Tsui Village, plus 14 households returning from overseas officially moved into the new town of Sai Kung.

The transition from Lan Lai Wan to Man Yee Wan

The new village is no longer called Lan lai Wan, it has been renamed as Man Yee Wan allegedly as suggested by Lee Siu Yum, “Our old village was a volcano millions of years ago, the beach was black in colour, so it was named Lan Lai Wan, of course, moving to a new village we like to start off with a name which means everything will be desirable.” The streets on the newly reclaimed area are named Man Nin Street, Yi Chun Street, Wan King Street and Sha Tsui Street. Since then the population in Sai Kung increased a lot and was renamed Sai Kung New Town. The area which was there even before the reclamation is now called the Sai Kung Old Market. For the villager’s eligible for compensation from the Government, they either started their own business or leased out property for a profit to start a new life, but the fact that farming was once their livelihood, they dare not forget.

In the home of a villager Lee Tin Chee, rice buckets and ploughshares are old treasures. “When we moved to our new home, the elderly insisted that we must bring them along.” Although they would not be able to do any more farming in Sai Kung New Town since the 1970s, these farm tools in fact played an important role. “As our custom of marriage, the bride must jump over the threshold entry with a red-hot ploughshare below, the newly-wed’s bedroom must have a rice bucket, covered with red paper, filled with rice and holding the wedding candles, symbolizing good health and prosperity. We kept the tradition even during my son’s wedding,” says Lee Kwok Wah.

New soil inherits old culture

Hakka people hold on to old traditions, after having moved away from the village for forty years, the villagers still return for ancestral worship every year during Chung Yeung Festival. In 2015, on the Sunday before Chung Yeung, Lee Kwok Wah in conjunction with Lee Chak Man (son of Lee Siu Yum) and his nephew Lee Sau Hong (brother of Lee Fook Hong) led dozens of people of the Lee clan into the restricted area of High Island Reservoir with a permit, set foot on the slopes and congregated in front of the worship graves to pay homage to three generations of their founding ancestors, and finally moved up to the Lee Clan Ancestral Hall on Muk Min Shan. After flooding the old villages to form the reservoir, four new ancestral halls for all the four surnames are built here side by side consecrated to all the ancestors.

“Our ancestors encountered a lot of twists and turns, even the genealogy records were destroyed during the war. In 1998 we went back to find our roots in the mainland, and to understand the migration of our ancestors from Huidong to Hong Kong. We are now writing a new record of our history which will of course include the last forty years when we had to move from Lan Nai Wan to Sai Kung Town.” Man and land, the two will inevitably continue to evolve. The Hakka ethnic group has the habit of migration since ancient times; they show us how to preserve old traditions in the face of change.